10/19/2013

Growing up in the US, you can only see a few types of battlefield firsthand: revolutionary war battlefields, which basically just look like fields. And civil war battlefields, which are mostly fields with a few earthworks thrown in (Vicksburg is an exception). You might also see French and Indian battlefields, or battlefields from the Indian Wars. I figured these were pretty different from modern battlefields.

Uniforms at the Ypres museum: German, UK, French, American. Click to expand.

One of my top goals in visiting Belgium was to visit a World War I battlefield (I also wanted to visit the Ardennes, sight of the Battle of the Bulge, but it was in a far corner of the country). I wasn’t sure if the World War I battlefield would be the same or different than Civil War battlefields.

Passchendaele, near Ypres, before and after the war. Those dots are craters.

My target was Ypres (pronounced ee-pruh), sight of some of the worst fighting in the entire first world war – Ypres was a battlefield for almost four years, divided into some five barely distinct ‘battles.’ Whereas a civil war battle was typically a one-day affair (Gettysburg was an outlier – open fighting lasted three days; the only longer battles I’m aware of were the extended sieges of Vicksburg or Petersburg). Although the numbers are impossible to pin down, more men maybe have been killed on the Ypres battlefield than in the entire Civil War (620,000 men were killed in the Civil War; the upper estimate for total casualties on Ypres is 1.2 million, of which maybe half were killed). That’s leaving out the hundreds of other battles – such as Verdun, the Marne, or the Somme.

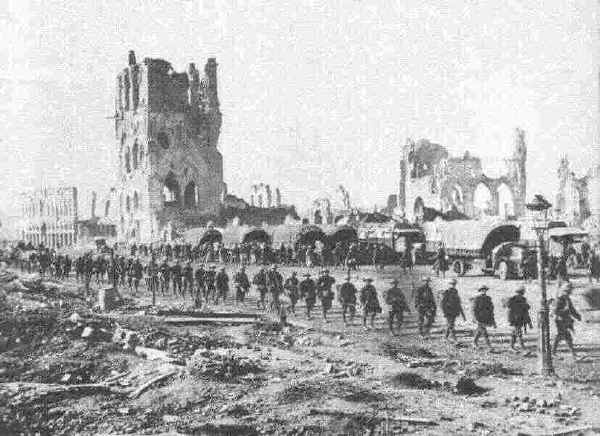

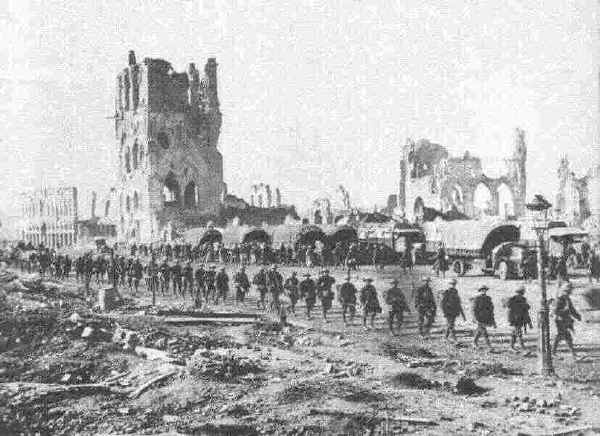

Ypres during the war

Not only did Ypres see intense extended fighting, it was also the sight of the first chemical warfare attack, ever. Also, Hitler fought there. Incidentally, if you’re unfamiliar with WWI, there’s an amazing 5-part soldier’s eye podcast produced by Dan Carlin that covers the war over the course of 15 hours.

The town today, looking toward the Menin Gate

Ypres was pretty close to Antwerp by train, so I took the train into the city center. The city as a sort of physical entity was pretty much obliterated during the war (it was a mid-sized cloth manufacturing town). Now, it looks pretty much like other Belgian towns, with a charming downtown that belies its bloody history.

The center, which was had a cute farmer’s market when I visited, also features an outstanding WWI museum, my first stop. It’s a pretty intense museum – there are lots of artifacts, videos, some gruesome photos, reconstructions of trenches. This is a part of the world where there’s still unexploded ordnance in farm fields, and where trench systems are still being uncovered.

After visiting the city, I started out on a tour of the battlefield with a few other people. The tour met by the Menin Gate, a memorial that commemorates 54,000 men from the British Empire whose graves remain unknown. There’s a ceremony here, every single night, to pay tribute to soldiers from the Empire who died in Ypres.

The battlefield during the war

The area around Ypres doesn’t look much like a battlefield. There’s no craters, and no sign of fighting at all. Most of the land is farms; it’s absolutely flat, enough that a 200-foot hill was a major strategic objective. It rained lightly during the tour, which felt fitting. Most of what you hear about the western front is mud. Because there was four years of fighting, and because men were confined to trenches by artillery fire, it was often impossible to move bodies. You dug a shallow grave, but when you left the front and another unit came in, and they needed to dig? The only gruesome option was to dig through the bodies from one or two or three years before.

Tyne Cote cemetery

Nonetheless, there are graveyards, and we visited three: a small and large English graveyard, and a German graveyard. The large British cemetery was Tyne Cot, with about 12,000 graves, with soldiers from the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and other parts of the empire. It’s hard to believe, but at this time, Newfoundland was a separate country from Canada, so you also see soldiers with Newfoundland flags on their gravestones.

South African gravestone, with Springbok

It’s a beautiful cemetery, on a slight rise, very peaceful. It doesn’t look like 12,000 men are buried here. We also visited the German cemetary of Langemark. German cemeteries in Belgium are something of a sore topic – or, at least, they used to be. After all, Germany invaded Belgium during the war, and there was a lot of bad blood between the two countries afterwards.

Langemark German Cemetery

The British cemetery, Tyne Cot, looked basically like an American military cemetery: rows of white stones, about 2 feet hight, with clipped green grass. It was familiar. The German cemetery was totally different: wooded, with black stones set into the ground. The stones aren’t for a single soldier. It’s common to see stones saying “7 unknown soldiers buried here.” But far and away the most striking thing was an empty square in the center of the cemetery.

“In a mixed grave, here rest 24,917 German Soldiers. 7,977 remain unknown.”

It’s surrounded by low stones, and a small metal wreath. If you walk around it, on the far side, there’s a small plaque that states simply that 25,000 soldiers are buried in the grave. I found this cemetery had a far more profound effect on me. Maybe it was how few soldiers were named, and how few soldiers had their own grave. And it also was different from other cemeteries I’ve visited, so I had to reconsider what it really meant.

It’s a complicated cemetery. Many of the soldiers who fought here were students; some were 15 years old. On the other hand, Hitler visited this cemetery. After all, he fought at Ypres and received a commendation for bravery. You can stand in front of a memorial, where he’s photographed standing during World War II, and wonder what you’re supposed to think.

The final stop, and my favorite on the tour, was some of the few remaining untouched World War II trenches. These trenches, which had been occupied by a unit from New Zealand, belonged to a farmer who took back the property after the war. He thought it might be worth preserving these, maybe to make some money, so he left them unchanged. Now they’re part of a little amateur museum.

Stereoscopes

The museum itself isn’t much: lots of old rifles, lots of helmets, bits of metal. Lots of stereoscope photographs of the war. Behind this museum are the trenches.

Craters near the trenches

It was raining while I was there. The bottom of the trench was muddy, filled with pools of water. Metal sheets lay against the edge of the trench, and there were big craters on either side. A forest grew around the trenches, which would never have been there during the war. But this was still far and away the most authentic-looking battlefield I’ve seen. It didn’t take a whole lot of imagination to think about what it would have been like to fight here.

Besides this little plot of land, the rest of Ypres, and the land around it, looks like farmland everywhere else. Like there was never a battle fought there. The only sign of fighting is what’s still below ground, and the dozens of cemeteries that dot the countryside.